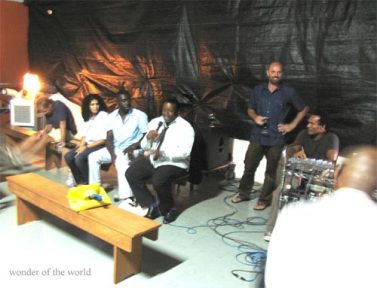

Isaac Julien, centre, next to Peter Doig at the Studio Film Club, Port of Spain for his premiere of Derek as part of the Trinidad Film Festival.

Derek, in chronological order, records the work and life that stands at the foot of Derek Jarman’s humour and spirit of being an artist. The filmmaker and actress, Isaac Julien and Tilda Swinton respectively, have produced and narrated a film on his life whereby the use of language is perpetuated to give some type of palpable meaning to British audiences alone, and to their own personal relationship with him.

Through his interviews, notes and film footage, Jarman concurs that his sexuality was deeply repressed, and this facet is the undercurrent that runs through his work and is the bases of his films, like Sebastiane (1976), which had British audiences eager to peek at two men frolicking on a rock. Derek showed rare 8 film footage of the artist and his journey into a series of experimental and time lap pieces.

At the Trinidad Film festival, Trinidadian audiences were privy to a man who expressed himself as who he was, and addressed subjects as sensitive and stigmatic as homosexually, HIV and of its oppression by the British government under Margret Thatcher. Jarman believed that film could be transcribed as painting and moreover understood his limitations as a painter. Film could transcribe into layering of the motifs that surrounded his inner infatuation of the self and self representation.

Isaac Julien’s objective is to arouse the interest and importance of his work to young British artists to a man who fought for his rights in the public eye, and lived the end of his life with dignity, acceptance and of his love of being. Julien’s documentary is to acknowledge Derek Jarman as one of the most influential filmmakers in British cinema.

Isaac Julien with the mike, Chris Ofili to his right, Peter Doig, standing, Che Lovelace from his left at the Studio Film Club, Trinidad.

Although of his importance as a contemporary filmmaker, Isaac Julien's production was compounded by an overly artistic and unmemorable monologue by Tilda Swinton which couldn't be understood as she wondered through the streets of London and at the subject's former cottage and stone garden. Derek failed to stimulate any interest at its premiere at studio film club during the Trinidad Film Festival. Eh, what de fock she manguing we with?

1 comment:

if you want to read the unmemorable monologue here it is in its entirety:

Letter to an angel

Derek Jarman's films were eccentric, beguiling and above all honest. We need his guiding spirit now more than ever, says the actress Tilda Swinton

Tilda Swinton

The Guardian, Saturday August 17 2002

Dear Derek, Jubilee is out on DVD. I found a copy in Inverness and watched it last night. It's as cheeky a bit of inspired old-ham, punk-spunk nonsense as ever grew out of your brain, and that's saying something; what a buzz it gives me to look at it now. And what a joke: there's nothing one-eighth as mad, bad and downright spiritualised being made down here these days this side of Beat Takeshi.

There's an interview with you at the end of the thing: a face-to-face. Very nice to see that face, I must say. Jeremy Isaacs asks you, last of all, how you would like to be remembered, and you say you would like to disappear. That you would like to take all your works with you and... evaporate.

It's a funny thing, because the truth is that, here, eight years later, in so many ways, you never could disappear, but - it has to be faced - in so many others you have. It has snowed since you were here and your tracks are covered. Fortunately, you made them on hard ground.

Well, I could tell you that we got some things right back then, sitting round the kitchen table in Dungeness, projectile-vomiting with the best of them: you were indeed the great Thatcherite film-maker - for every £200,000 film you made, real profits were seen (by someone or other) within at least the first two years; and all those royal circus brides did end up cutting themselves out of their wedding dresses and looking into the camera. Alan "all film is an advertisment for something" Parker did end up running the BFI and dissolving its production arm; and FilmFour was just a flash in the pan.

They talk about the British film industry a lot these days. You remember that renaissance they all got moist about in the 1980s after Chariots of Fire won four Oscars - "The British are coming"? And then that thing with Henry V? Well, the renaissances are rolling themselves out pretty much yearly now, as director after director makes his or her first film and then graduates to making commercials.

It felt as if industrial films on these islands in those 1980s were made by people who could not quite get into television. Or by shameless, traitorous expatriates who had legged it for the "free world". In those days, British Film Inc, when invoked, meant getting proud about The Lavender Hill Mob or Whisky Galore! An American-Indian partnership began to give Britain an exportable identity: these were the Crabtree and Evelyn Waugh days of post-imperial mooning about, when nostalgic dreams of the Grand Tour meant film culture to a lot of people. Class obsession - still the greatest stock in trade of industrial cinema here - began to show a profit.

I had run away to join a different circus myself: Planet Jarmania. You were the first person I met who could gossip about St Thomas Aquinas and hold a steady camera at the same time. I thought it would be good to hang out with you for six weeks: I guess we had things to say. Our outfit was an internationalist brigade. Decidedly pre-industrial. A little loud, a lot louche. Not always in the best possible taste. And not quite fit, though it saddened and maddened us to recognise it, for wholesome family entertainment.

Wholesome families were all the rage then. There was a fashion for a thing called "normal" and there was a plague abroad called "perversion". There was no such thing as society, and culture meant something to do with yogurt (this was before the Sunday Times educated us that culture means digested opinions about marketable artistic endeavours). Things are different now: people (at least pretend to) have an enormous amount of sex and tell everybody else about it. We use the word terrestrial without a flicker of spacethink. People cook and decorate their flats and celebrate the millenium and the opening of the Commonwealth Games in cajun/Echo Park hacienda/Alternative Miss World circa 1978 styles. Straight has started to mean honest again, getting very drunk is hilariously funny and smart, and newsreaders would refer to today as July seventeenth.

We used to be referred to as the arthouse; how it used to irk us then. How disparaging it sounded; how sickly and highfalutin; how pious and extracurricular. For arthouse superstar, read jumbo shrimp. Yet, then, as now, the myth prevailed that there was only one mainstream. We were only too happy to know that our audience existed and to hoe the row in peace. Nobody here paid that much attention to us, that's true: no one ever thought we might make them any money, I suppose.

What grace that constituted. Not to be identified as national product. The intergalactic BFI. ZDF in Germany. Mikado in Italy. Uplink in Japan. This was our nation state: this was continuity. We sneaked under the fence, looked for - and found - our fellow travellers elsewhere. Here's the thought: slice the world longways, along its lines of sensibility, and not straight up and down, through its geographical markers, and company will be yours, young film-maker. Treason? To what?

The dead hand of good taste has commenced its last great attempt to buy up every soul on the planet, and from where I'm sitting, it's going great guns. Art is now indivisible from the idea of culture, culture from heritage, heritage from tourism, tourism from what I saw emblazoned recently on the window of an American chain store in Glasgow - "the art of leisure". That means, incidentally, velours lounging suits by the ton.

The colonial balance has shifted and the long spoons are out. We now stand shoulder to shoulder with something identifiable as civilisation itself, or else... Security never felt so much like a term of abuse. I was in Los Angeles earlier this year and was asked by a jeweller's assistant in an emporium on Rodeo Drive if the reason I declined to wear a stars and stripes jewelled badge on my front at a public event was that I was "an Afghani bitch". You may not need me to tell you about the fight for civilisation afoot these days. More of the same, but worse than even you could have imagined. Meanwhile, in a binary world, we on these islands cream on creamily up a Third Way.

Things have got awfully tidy recently. There is a lot of finish on things. Clingfilm gloss and the neatest of hospital corners. The formula merchants are out in force. They are in the market for guaranteed product. They go out looking for film-makers with the nous of one who might consider employing halogen spotlights in the hopes of attracting wild cats into a suburban garden. They are missing the point. Don't they know the roulette wheel is fixed? That the croupier is a cardsharp? Do these people not watch old movies? It's the spirited that hold the hands in the long run, it always was - the low-key for the long term, the irreverent, the cheats, the undaunted and inspired rule-breakers, not the goody-goody industrial types with their bedside manners and managerial know-how.

It is all done with smoke and mirrors, and it always will be. Not with memos and steering groups. Not with statistical evidence or test screenings. Don't they know the basic laws of being in an audience? That we say we want to know more about the villain, but we don't really; that we say we like happy endings, but our souls droop without the bittersweet touch of something we might recognise, as we bend from our fascinating and complex mortal world into the virtual dark and back again. That we say we want famous faces we can recognise, but there's one thing that a face that we identify as an actor's first and foremost cannot do for us that the face we might see as that of a person can do. It is human beings that are of use to us in the figurative cinema. Human shapes and gauchenesses and human passions. Not drama and perfect timing and a well-tuned charisma round every bend.

I have always wholeheartedly treasured in your work the whiff of the school play. It tickles me still and I miss it terribly. The antidote it offers to the mirror ball of the marketable - the artful without the art, the meaningful devoid of meaning - is meat and drink to so many of us looking for that dodgy wig, that moment of awkward zing, that loose corner where we might prise up the carpet and uncover the rich slates of something we might recognise as spirit underneath. Something raw and dusty and inarticulate, for heaven's sake. This is what Pasolini knew. What Rossellini knew. This is also what Ken Loach knows. What Andrew Kotting knows. What Powell and Pressburger, what William Blake knew. And, for that matter, what Caravaggio knew, painting prostitutes as Madonnas and rent boys as saints. No, Madonnas as prostitutes and saints as rent boys - there's the rub.

I think that the reason that you count for so much, so uniquely, to some people, particularly in this hidebound little place we call home, is that you lived so clearly the life that an artist lives. Your money was always where your mouth was. Your vocation - and here maybe it helped a little that you offered that special combination of utter self-obsession with the appearance of the kindest Jesuit classics master in the school - was a spiritual one, even more than it was political, even more than it was artistic. And the clarity with which you offered up your life and the living of it, particularly since the epiphany - I can call it nothing less - of your illness was a genius stroke, not only of provocation, but of grace.

Your gesture of public confessional, both within and without your work - at a time when people talked fairly openly about setting up ostracised HIV island communities and others feared not only for their lives but, believe it or not, for their jobs, their insurance policies, their friendships, their civil rights - was made with such particular, and characteristically inclusive, generosity that it was at that point that you made an impact far outspanning the influence of your work. You made your spirit known to us - and the possibility of an artist's fearlessness a reality. And the truth of it is, by defying it, you may have changed the market as well.

That earlier Jubilee year you gave us prophecy - painting extinct in Paranoia Paradise, the generation who grew up and forgot to lead their lives, the idea of artists as the world's blood donors, history written on a Mandrax, fear of dandelions - and yet, like Carnation from Floris, not all the good things have disappeared.

Maybe now it is as bad as you and I used to say it could possibly get. Maybe it's worse. But here we are, the rest of us, tilting at the same old, same old windmills and spooking at the same old ghosts. And keeping company, all the same. It's a rotten mess of a shambles, you could say. It's driving into the curve, at the very least. Some would say you are well out of it. I reckon you would say: "Let me at 'em."

The challenges facing a film culture today? The possibility of film-makers losing the use of their own spirits. The paralysis of isolated, original voices. The existence of the student loan in the place of the student grant. The rarity of distributors with kamikaze vision. Too many conference tables. Too few cinemas. Too little patience. Pomp and circumstance. The concept of the "successful" product. The idea that there is not enough to go around. The eye to the main chance. The substitution of codependence for independence. The idea that it has to cost millions of pounds to make a feature film. The idea that there is only one way to skin a cat.

This is what I miss, now that there are no more Derek Jarman films: the mess, the cant, the poetry, Simon Fisher Turner's music, the real faces, the intellectualism, the bad-temperedness, the good-temperedness, the cheek, the standards, the anarchy, the romanticism, the classicism, the optimism, the activism, the glee, the bumptiousness, the resistance, the wit, the fight, the colours, the grace, the passion, the beauty.

Longlivemess.

Longlivepassion.

Longlivecompany.

yr,

Til

Post a Comment