An open discussion on Jackie Hinkson's work, Stations of the Cross, Port of Spain, 2005

The visit to Mr. Hinkson’s home one Friday afternoon to see him in his studio, was a treat. As always he was busy and physically moving around. He is a very agile person despite his protest of age. The body of work that he showed was clearly the product of several years of diligence and is awe inspiring in terms of size, scale and scope. I was not a fan of Mr. Hinkson’s work. For many years I found that his was work that I liked sometimes and other times found great fault with. The fault I found always had to do with application, and almost always they were to do with his paintings. Mr. Hinkson has produced work in many media. He is known for his watercolour paintings of landscapes and seascapes. But his most frenetic are his charcoal pencil drawings. He has many large canvases of works on charcoal. With those pieces I always felt satisfaction because of the lyrical, rhythmic nature of them. In other words I could relate to them. With his colour work I had more reservations.

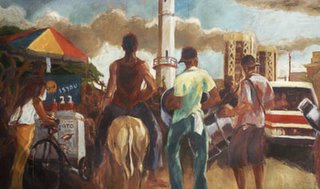

Stations of the Cross, Christ entering Port of Spain

Then in 2001 I was on a workshop with Mr. Hinkson and I saw another side to him. The workshop featured artists who were basically between the ages of 26 to 38 from Trinidad and Tobago, the region and the world, including India and Africa. Mr. Hinkson was the most senior artist chosen. In fact I was asked more than once what was the motivation to include such an ‘old’ painter, because I was on the working group to coordinate the workshop. A curious question, as Mr. Hinkson seemed to thrive in that ‘youthful’ environment, and he certainly did not seem to mind being around young people, whom he could have easily found tiresome and arrogant. For us in Trinidad and Tobago the artistic divide is filled with many prejudices, particularly that of ageism and entitlement, but that is another article. What I saw from Mr. Hinkson at the workshop was someone who’s curiosity was very much honed by his environment and interest in working on something every day. He is disciplined and methodical, quiet and thoughtful. He is neither flashy, showy or boorish. He is humble and intimately involved in the pursuit of painting. This ‘old’ painter had a lot to show us ‘younger’ artists, I came to realize very quickly.

At the National Museum of Trinidad and Tobago

The workshop left a profound impression on us all, and after two weeks of focusing on art, we disbanded, but kept in touch as time permitted. It was at this time that Mr. Hinkson began a new body of work. Trinidad was changing rapidly before all of our eyes. We were reeling from front page murder reports and kidnappings and a visit to church sparked the idea that stay with him as he looked around at our changing landscape and the concept was born.

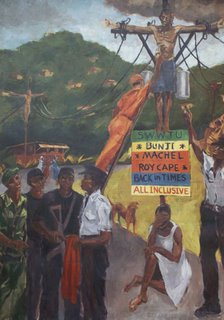

He says that as he looked at the friezes in the church he thought of the great masters of Italy and France. Artists died for centuries who provided the mastery that encouraged generations of devotion to the church. The ideas came thick and fast, the savannah, the trees, the rum shop, the party banners, the common things of everyday life against the bitter, the sad, the sublime nature of things. He would do this, and he would work at a scale that was comfortable for him, and that was life size.

Judas and Christ infront of the White Hall, Port of Spain

Mr. Hinkson’s colour palette is one that has been keenly shaped by several decades of painting the Caribbean. His has a particular sensibility to light. I believe that no other West Indian painter has painted so much of the region, at least not over so many years. Also his tendency is to work with a drier, less loaded brush than say a Lisa O’Connor who also paints landscapes and seascapes. He does not overpaint, but applies pure colour to his surfaces. Some of his paintings have the shorthand of his sketching. The way the paint is applied across the surface of the canvas is akin to the broad strokes of charcoal of his black and white works. That does not make it any less challenging to me to look at sometimes. It is a matter of preference and that is all it is.

The fishermen in distress

I harp on it because it always affects how I view his paintings. That said, his series of canvases loosely based on the Catholic Stations of The Cross, is an ambitious affair. The very size of the works and the juxtapositioning of folklore and carnival with political imagery and brand name products is mutli layered with meaning. My issues with the work has to do with perspective. Unlike when he paints with watercolours, where this issue almost never occurs, I find that in many instances the pieces appear flat because everything on the picture plain is handled with the same degree of interest and choice of colour and application, and I would like to see more space and depth of field. But again this is a preference on my part, as the Post Impressionist painter Gaughan’s work has the same decorative, flat quality about it and does not suffer for it in the least, and he was a master in his field. But closer to home, the same can be said for many of our older ‘master’ painters works, like Carlyle Chang and Boscoe Holder, their work too has that flat decoration to it. But it is not only the older artists, the work of Nicolai Noel has its moments as well to take on such a bend.

Mr. Hinkson’s acrylic pieces try to remain light however and this is a large part of the works appeal. His shades of green anchor his works and set off the vegetation that is punctuated with bare backed men and armed policemen, telephone poles and street signage.What is important about this work is its very ambitiousness. Few artists work at the size that Mr. Hinkson has for this body of work. Leroi Clarke and Eddy Bowen are the only two who work consistently large. But it is not just about the size of the work, it is also about content. His navigating his spaces by including many aspects of life in Trinidad and Tobago, real or imagined and how they are melded together on his canvas, folkloric imagery sharing space with the Christ figure alongside a man holding our trademark beer in his hand for example. He is grappling with the unique space that is Trinidad and Tobago. He is not saying that he has the answers, but saying that he sees and he wants us to see too.

The crucification at Laventille

When I met with Mr. Hinkson on that Friday, we sat and talked for some time. He had just come back from an extensive European tour and a large part of what was said centered around the works of the master painters he saw and the impact it made on him. He said that in processing all that he had seen, he felt regret for all that he had done with his work, he found that he had not broken the surface of what he should be leaving behind, and that art is not about discussion or theory, but of the doing of it for itself.

One statement stood out the most however and that was how much the intent of the masters had impacted on him. He said that he had seen a lot of contemporary works and they were strong at first, but after the first impressions the technical skills proved less enduring than the works of Goya or Titian, Bosch or Grugel came away from our conversation quite satiated by all that we had tackled about Art’s purpose in the world and its impact on our tiny island republic and concluded that what makes Mr. Hinkson one of our true pioneers is that he is willing to see himself against these great artists and still find so much needed in himself.

At a time where everyone in Trinidad and Tobago who draws a straight line and gets it seen calls themselves an artist with such speed, Mr. Hinkson is a worker, an artist who is the real died in the wool thing. There is no fanfare to the very hard days work he puts into what he does. He is not waiting for the accolades, he is not working to impress the German collectors or trying to please the next nouveau riche Trini who comes along. His is a steady and true vocation and he understands that every work is not a masterpiece, but he endeavours to try. He commits to the journey and he perseveres. - Adele

Friday, December 09, 2005

Finding a stage for “Christ in Trinidad”

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Disclaimer:

Views expressed on thebookmann are not affiliated with any Art Organizations and an “Art Review” may be open to interpretation as it is an observation at face value.

Amendments to such articles if misleading or with grammatical errors shall be corrected accordingly.

All photographs, Feinin studies, accompanying quotes, articles and visual headers appearing on site are the exclusive property of Richard Bolai © 2004 - 2010 All Rights Reserved.

Any fare use is restricted without written permission

Amendments to such articles if misleading or with grammatical errors shall be corrected accordingly.

All photographs, Feinin studies, accompanying quotes, articles and visual headers appearing on site are the exclusive property of Richard Bolai © 2004 - 2010 All Rights Reserved.

Any fare use is restricted without written permission

No comments:

Post a Comment